Test Match Therapy: The Greatest Escapes

0England at Wellington, January 20-24, 1984

NZ 219 & 537

England 463 & 69/0

Match drawn

What a Test Match this was.

I can remember feeling completely drained by the time the umpires finally pulled stumps late on the fifth day of this epic contest. New Zealand had first been forced to push the rescue button three days earlier, which now seemed a lifetime ago. Not because it was dour, as a lot of these rescue jobs are, largely out of dogged necessity, but rather because it was full of such taxing drama and outstanding cricket. The entire Test was. It was a thing of constantly moving parts and changing fortunes, marked by some great individual performances. If ever an American were to ask me what is the point of five days of cricket without a result at the end of it, I would tell them to go and watch a full replay of this game. Of course, the American would not get past the first half hour. But this match was cricket porn for people like you and me.

New Zealand’s first innings was shaken and rattled by Ian Botham at his absolute best with a cricket ball in hand. It was hostile, aggressive and penetrating, his 5 for 59 ripping the heart out of the New Zealand batting line-up. Bob Willis was also lively and England eventually managed to dismiss the home side for 219 on what would prove an excellent batting surface.

Then it was the turn of Bernard Lance Cairns. Cairns was more shuffle and wobble than hostile and aggressive, coming as he did off that short run-up and bowling off the wrong foot with both arms aloft. But he just adored the Basin Reserve. With the bat he seemed to have a personal mission to become the first person to not just clear the Eastern embankment but also get the ball into the mouth of Mt Victoria tunnel. And with the ball in hand he revelled when the northerly wind blew across the pitch or some cloud cover came into play. And when he got both at once, the ball would swing like Hugh Hefner in the Playboy mansion.

Everything was going to plan for New Zealand when Cairns completed his five wicket bag and reduced the tourists to 115 for 5. Who needs Richard Hadlee? Well, it was almost impossible to keep Hadlee out of any game, and the Basin had gasped in awe when the former Southern League goalkeeper pulled off the most incredible flying catch in the gully to dismiss the always dangerous David Gower. Hadlee had already taken another stunner in the gully and Martin Crowe also held a ripper close in, leaving the large Saturday afternoon crowd abuzz.

This was a brilliant performance in the field led by the folk hero Cairns. He was clearly enjoying himself, the big grin making several appearances throughout the afternoon. And there was even Test wicket number 100 to celebrate as well. What a day, he must have been thinking as he stood at third slip shortly after taking wicket 101. Probably thinking about it too much, however, because he then dropped an absolute goober. And it was Ian Botham on 0. That could prove costly, I can remember thinking to myself at the time.

Cairns would get his man in the end. A day later. I.T. Botham c. J. Crowe b. Cairns 138. England 347 for 6. And the irrepressible Derek Randall of Nottinghamshire chimed in with 164 of his own as England powered away to a first innings lead of 244. It was terrific batting to watch from two of England’s finest, but constantly set against the gnawing backdrop of If Only.

New Zealand now had a mammoth task ahead to try and save this Test. The best part of half of it still remained. Edgar and Wright were as solid as ever but not for long enough. Things did start to look promising when Geoff Howarth and Martin Crowe managed to get on top of the bowling and took New Zealand past 150. Then disaster struck. Howarth fell victim to that cruellest of dismissals: a powerful straight drive from Crowe deflected by the bowler’s hand onto the non-strikers stumps, the New Zealand captain backing up too far and short of his ground. There were no replay screens in those days and, up on the bank, I was left bemused as to why the England players were all celebrating and a deflated Howarth was soon walking off.

Jeff Crowe came and went, and I sensed it was all but over when the lanky figure of Jeremy Coney appeared out in the middle. Coney was a useful cricketer, no question, and had already earned an Emergency Services badge with a number of useful rescue acts for New Zealand. But meritorious as those were, he was out of his depth here. By my calculations he would need to score a hundred at the very least. Not only had he never scored a Test century, but he had not managed a first-class hundred for seven long seasons. Sobering to think that batting partner Martin Crowe was 14-years old when Coney last passed three figures.

And Crowe himself had yet to score a Test hundred as well. In fact, the boy wonder was attempting at the time to resurrect an international career that had threatened to be crushed early by too heavy a weight of expectation.

I am just eternally grateful that Monday January 23, 1984 happened to be Wellington Anniversary Day. Because it meant I was there to enjoy the day when the shackles finally fell from Martin Crowe’s broad shoulders; and that so many others also had the opportunity to eventually stand and applaud an innings of immense class. A star was reborn.

My abiding memory of that day was the cracking sound of the ball coming off the middle of Crowe’s bat, reverberating around the Basin amphitheatre like a shotgun. There was always something so graceful about Martin Crowe when he was in this mood. The way the big man would just lean forward into the ball and send it tearing across the outfield. The familiar straight drives were mixed with imperious driving through the covers and fast, powerful pulling off the back foot. No offence to Turner or Williamson, but Crowe was always the best to watch. It was the way he managed to successfully mix brute power with impeccable timing, balance and grace.

People like us merely dream of scoring a Test century. Crowe would have spent his whole life envisaging the moment. And when it finally came, all 19 boundaries of it, the significance of the occasion clearly took a toll on him and his concentration, as he was immediately dismissed when fiddling at a ball from, of all people, Mike Gatting. Crowe’s demise at the hands of the tubby part-timer felt like a criminal act. It was as if the most magnificent of operatic performances had suddenly been gate-crashed by a pantomime buffoon.

And it left New Zealand still in peril. Coney now had to take over the controls. And he did. It was clever cricket by one of great thinkers of the game. He mixed resolute defence with intelligent turning over of the strike and the odd vicious pull shot or impressive square cut. He nursed New Zealand through to stumps at 335 for 7. He would resume the next day on 76 and still facing further salvage work.

Ian Smith and Coney started Day Five well and took New Zealand’s lead through to 158 before Smith departed. It was still not enough. Then came yet another turning point in the game. And, once again, featuring Lance Cairns.

I often wonder how the advent of technology into professional sport has impacted the record books. Those decisions which are now overturned or changed by people sitting somewhere in a booth have no doubt impacted on many games, results or careers, just as the lack of it once did, only in an opposite fashion. Cairns was struck on the pads by off-spinner Nick Cook before he had scored. It kept low and looked absolutely plumb. But the umpire neglected to raise his finger. There was no ball tracker in those days, but there were television replays. And with each replay it looked more out.

The record books now show Cairns making 64 that day and batting long enough with Coney to both save the Test and set a new record ninth-wicket partnership for New Zealand.

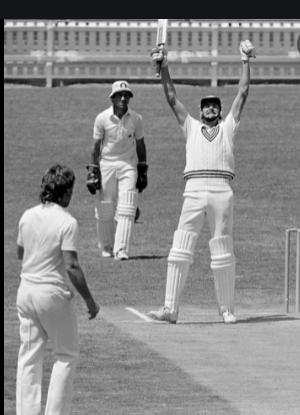

Coney ended 174 not out in what was one of the great Test innings played by a New Zealand batsman. A mixture of craft, control and perseverance, few will forget the sight of him standing in the middle of the Basin Reverse with both arms pumped aloft when he reached his maiden Test century,

And to that American, or anybody else for that matter, who cannot see the point of five days of cricket without a result, I would point out that New Zealand went on to win in Christchurch, draw in Auckland and therefore win its first Test Series against England. An historic outcome for the game in New Zealand – all made possible by five days of resultless but unforgettable cricket played in Wellington.

Follow Euan on Twitter