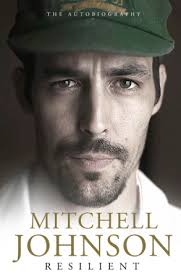

Mitchell Johnson: Resilient

0This is arguably the most Ocker book of all time.

Mitchell Johnson sets the scene in the first chapter. He was erratic, he got that, and he moved on.

Will it be the one who broke both of Graeme Smith’s hands (sorry about that) and terrorised South Africa, or the one who the Barmy Army wrote that song about? You know the one: He bowls to the left, he bowls to the right, that Mitchell Johnson, his bowling is shite”. I am asking myself the same question.

His upbringing in Townsville was as close to outback living as you could get. He had mates called dingo and Horse and tried his hand at most sports, with a promising career in tennis, where he played right handed. He only started playing cricket when he was 17.

He also took up javelin, and with a throw of 55 metres got to represent his school in the Queensland champs.

I choked. Massively choked. There were all these kids there who had been doing it all their lives and they had shoulders like swimmers and elbows all strapped from years of throwing. I was so tense I don’t think I threw more the 40 metres. It was pretty embarrassing. But at least I got a day off school.

That sums up his self-effacing reflection of his life.

So how does a boy who took the game up at 17, and from the outpost of Townsville end up in the Australian system? He went to a Dennis Lillee coaching session in Brisbane and got noticed. The next week he was at a camp in the Academy in Adelaide, where he was treated with suspicion by those who had grown up playing in various age group teams. He didn’t even have any cricket boots.

Lillee would continue to be a large factor in his career, following the concept of TUFF; tall upright, front foot.

Following some Australia “A” tours, and a year of first class cricket came the stress fractures, and two years out of the game. The turning point was when Queensland dumped him from their contracted players. Suddenly he got angry, and took his rehabilitation more seriously. And there is nothing quite like an angry fast bowler.

His takes on fellow players are interesting, and reveal his outsider status. He didn’t like rooming with Shane Watson because there was room enough for only his toothbrush in the bathroom. And when first joining the Australian team Shane Warne took him aside for two hours to practice on his … autograph.

Johnson’s career coincided with a tumultuous period in Australian cricket. There was Monkeygate and the tense relationship with India which went totally over his head.

There was Homeworkgate in 2013 where he felt he was caught in the crossfire of the Clarke v Watson spat. Predictably he didn’t really do assignments. Being publicly punished like that knocked him; he was not someone who got involved in politics (although he was clearly on Katcih’s side in the clash with Clarke).

And then there was the passing of Phil Hughes which triggered his retirement.

Then there is engagement with the Barmy Army. On some days they got under his skin (normally when carrying an injury) on other days it motivated him.

The 2009 Ashes tour was when he started to have confidence issues after a spectacular start to test cricket. The public spat between his mother and wife popped up just before the first test and he is open about how that got to him (along with a special piece of needling from KP).

It was a miserable series where he lost all rhythm as a nation swooped. The Barmy Army sang from the stands, and the English players sang the same songs on the field. And it worked.

It’s an interesting tale of a career that had more than its fair share of ups and downs on and off the field, while the side lurched from triumph to drama.

And hopefully a legacy of this book will be the term ‘sweat band swinger”. That’s what the likes of Johnson call those who bowl in the 130kphs.