Test Match Therapy: The Greatest Escapes 2

0By Euan McCabe

West Indies at Wellington, 20-24 February, 1987

NZ 228 & 386/5

West Indies 345 & 50/2

Match Drawn

The 1979-80 Test series between New Zealand and the West Indies produced the most controversial and dramatic cricket ever played in this country.

Clive Lloyd’s West Indians arrived as the leading team in world cricket but were to depart with a reputation in tatters and an unexpected place in cricket history as the first visiting team to ever lose a Test series in New Zealand. Even after allowing for the narrowest possible New Zealand victory in Dunedin and some inventive umpiring from Fred Goodall in Christchurch, this was a boil-over of almost Biblical proportions.

It also kick-started a golden era in New Zealand cricket. A side that had not won a series before at home, New Zealand would not lose another one here for a further 12 years.

In the midst of this unprecedented run the West Indies returned in 1986-87 to play a three match series which was billed at the time as the unofficial World Championship of Test Cricket. There was no ranking system in those days, but most people outside of Australia accepted that these were the two best sides in the world and this series would largely determine in what order they sat.

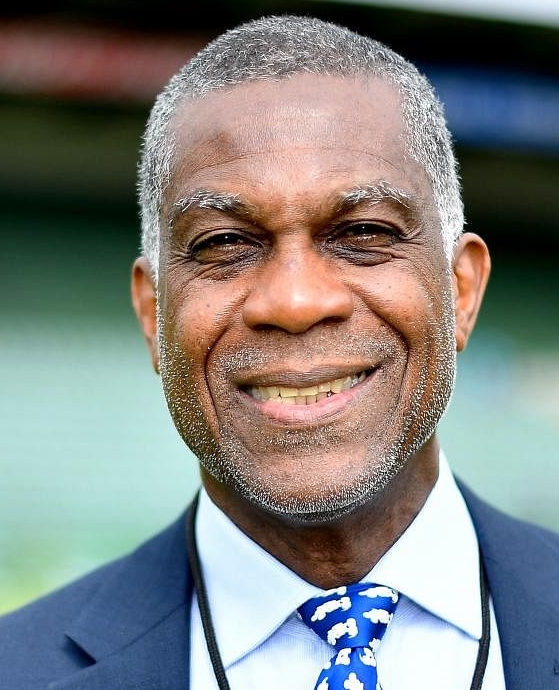

Sir Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards is an immensely proud man. He arrived in New Zealand leading a West Indian side full of names that struck fear into their opponents and a determination to put right the result of seven years earlier. Adding further fuel to what was already a potentially explosive mix was New Zealand’s ongoing rugby relationship at the time with Apartheid South Africa, an issue which had caused deep resentment in West Indian cricket circles for a long period of time.

Despite New Zealand’s record at the time, the West Indies began the series as favourites. Most sides would with a bowling attack consisting of Garner, Marshall, Holding and Walsh, and a batting line-up with names in it like Greenidge, Haynes, Richardson and Richards. New Zealand, meanwhile, was still coming to terms with the unexpected early retirement of Bruce Edgar, an opening bat with the mindset and technique to survive against that Windies bowling line-up. Scoring runs, or surviving long enough to score runs, was always going to be New Zealand’s biggest problem.

And so it panned out when the series began in Wellington on a typically fine day. Richards won the toss, inserted New Zealand, and then spent a relaxing day in his armchair at slip, rotating his armoury with despotic pleasure as New Zealand laboured with a mixture of grit and impending doom to reach 205-8 at stumps.

The Test was effectively over by stumps on the following day: The West Indies 218 for 2 in reply to New Zealand’s 228. And if it was not over then, it certainly appeared so just prior to tea on the next day, when the relatively new but already dated Basin scoreboard read New Zealand 228 and 20 for 2, West Indies 345. This Test could potentially be over by stumps on the third day, just over two hours away.

But Martin Crowe had joined John Wright in the middle and New Zealand’s two best batsman – and last remaining hope – at least managed to take the game into a fourth day by successfully surviving through to stumps, New Zealand ending at 91 for 2.

I watched Viv Richards stride off at the end of the day. There was something distinctly Napoleonic about the great Antiguan. For although squat in stature amongst his towering colleagues, he walked with an aura of such supreme self-confidence that it set him apart from other mortals and made him the undisputed leader of these men. Great leaders make statements without words. They also know the result of the campaign before it even starts. And it shows. To everybody; their men and the enemy. I imagine that if Napoleon Bonaparte had played cricket he, like Richards, would have refused a helmet when batting.

The fourth day had a much different feeling to the previous three. A powerful and bitterly cold wind now rattled through the bones of the Basin Reserve, whipping along an endless procession of low dark cloud, producing beneath it a brooding and gloomy amphitheatre which clattered loudly with the sound of flapping sightscreens. This promised to be a tough day at the office for all concerned.

The previously sun-drenched and heavily-populated eastern embankment of Friday, Saturday and Sunday had become by early Monday a desolate and deserted place that even Captain Oates would have declined as an option. As a result, the crowd, small in number on this bleak Monday morning, had all retreated through necessity to the relative safety of the old stand.

There we sat. Surely the most tragic of all cricket tragics. It was like being cast in a Tolstoy war novel. Marooned in a wintry Russian railway station as the snow gradually piled up outside, awaiting an unlikely rescue. All huddled together in close proximity, attempting to stave off the bitter cold inside and the inevitable defeat outside. There was even a suggestion at one point that we should break up some of the wooden seats in the stand and start a fire to enhance our prospects of survival.

Peering out of the railway station window we could see the battle slowly unfolding out on the windswept tundra. There was almost a run out in the very first over of the day, as Wright and Crowe grappled with how to successfully complete a run when one had the howling wind behind him while the other faced a lengthy uphill battle into it. And Wright was then dropped twice by the usually reliable Jeff Dujon, leaving us in the railway station to speculate that maybe this was one battle beyond even the Great Warrior opening batsman; that perhaps instead he preferred the safety of the Basin changing rooms.

But Wright and Crowe somehow made it to lunch. New Zealand was 141-2, meaning a small lead had been established. And only five sessions now remained. The mood in the railway station had lifted. Slightly.

Richards, meanwhile, was finding the wind hugely problematic as well, unable to decide who should bowl into it. The West Indies did not do spin in those days, so he opted, like all great leaders, to do the job himself. But also like many great leaders, there comes a time when the indefatigable self-belief becomes a stubborn buttress upon which defeat slowly propagates in the face of the blinding obvious. He just kept bowling and bowling into the wind, declining the new ball not just once, but again when a further 80 overs came and went.

Crowe and Wright just carried on battling the physical and cricketing elements, their scorched earth tactics eventually leading to a point where the enemy was forced into gradual retreat. All that was missing was the 1812 Overture.

A weary Crowe finally became Richards’ first victim, but only after he had batted for 385 minutes, scored 119 and shared in a record New Zealand third-wicket partnership of 241 with Wright. New Zealand was 272 for 3 when stumps were drawn and we were finally rescued from the railway station and sent home to our surprised families.

Wright just carried on the next day, this time in bright sunshine. There was a point when you thought the game would end and a punch-drunk Wright would need to be talked off. But his vigil finally ended when he returned a catch to part-time spinner Larry Gomes. He had scored 138 runs off 485 balls in 582 minutes. 18 minutes short of ten hours, it had become the longest Test innings ever played in New Zealand.

He and Crowe had saved the Test. And the series as it turned out, which eventually ended up at one apiece after the West Indies won in Auckland and New Zealand won in Christchurch.

A player of Martin Crowe’s ability is armed to survive such exacting examinations. Batsmen of his class even manage to somehow appear relevant in the most turgid of circumstances.

But John Geoffrey Wright?

He was a man who walked with a bow and often appeared to struggle when forced to run. And during that series he donned car mats to combat the inevitable blows to the upper body, leaving him wandering about the crease like the Michelin Man. But he was also a fine batsman who stored the shots away and battled hard for his country over a long and distinguished career as an opening bat, that most difficult and demanding of Test cricket’s numerous challenges.

Still, the resources and willpower he found to survive the opposition, the match situation and the weather over the course of those three days at the Basin Reserve in 1987 was the stuff of fiction.

This was an innings of Tolstoy proportions. And those of us fortunate enough to be marooned in his railway station will never forget it.

Follow Euan on Twitter