The Beat Grows Louder…(1991 and Beyond)

0Bose relates that ‘In Indian eyes, for all the talk of the spirit of the game, there was the hard-edged realization that the game could be a great vehicle for material advancement’.

In 1991, just four years after hosting the World Cup came three events, which when put together created a perfect storm that began turning Indian cricket (more so than cricket in India- the former pertaining to the national body, rather than the sport as a whole entity), into a bona fide economic and influential powerhouse of the sport. Interestingly, two of these events developed out of very negative circumstances.

First of all, in a drastic measure to prevent (so it is said) the country from falling into a state of bankruptcy, the World Bank ordered the national economy to be opened up to foreign investment. A previously very closed, perhaps almost secretive market place was now very quickly laid bare, and was very open to all.

Secondly, when George Bush senior took the USA into Kuwait to drive back Hussein’s Iraq in what became The Gulf War, the round the clock CNN coverage of the battle ensured that the sales of television sets in India suddenly skyrocketed, significantly not just within big cities, but villages also. A staggering statistic is that when the Australian entrepeneur Kerry Packer launched his television-driven rebel cricket circus in 1977, Cricket still hadn’t ever been televised in India.

On the subject of Packer, the Indian team captain Sunil Gavaskar was stripped of his post for daring to have contact with Packer. Packer himself never actually recruited a single Indian player. This was quite possibly a reflection of the almost disdain that the Indian Board had for one-day cricket at the time. In fact India had never won a match against one of the test playing nations at the World Cup until their 1983 triumph. Then, practically without warning in that tournament they beat the two-time defending Cup champions, the West Indies not once, but twice.

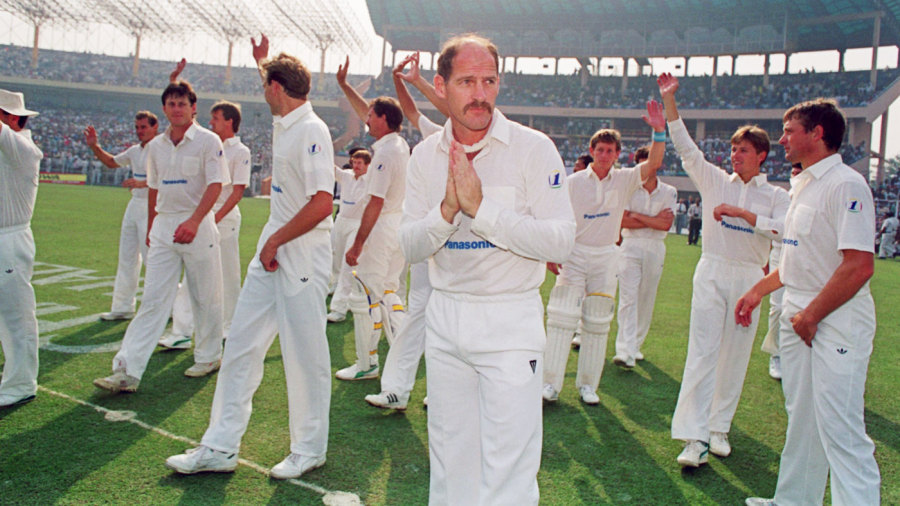

The third event in 1991 that was to ultimately change the course of world cricket power brokerage came when South Africa, returning to international cricket now that apartheid was no longer entrenched as a government policy, toured India for a series of one-day matches. It was the first time the Africans had played a nation of non-whites.

When some South African television officials asked the Indian Cricket Board how much they needed to pay for broadcasting rights, the Indian Board suddenly became aware of the unused goldmine they had been sitting on for years. ’Doordashan, the state broadcaster had televised domestic cricket and, far from paying anything, had often demanded fees from the Indian board to cover the cost of production.’ (Bose).

Then a rival South African channel entered the bidding race. Incredibly, the result was that no-one on the whole Indian board knew that the Board itself actually owned the rights to all television coverage of cricket. They had, in effect, been ripping themselves off for years. In his book, Bose says that when the Board finally came up with what they thought was probably a hopeful figure, they were shocked to discover that one of the bidding channels had ready an offer of about ten times as much. In a NZ farming vernacular, one might say the Indian board owned the prize cow of the herd, but had never once even attempted to milk it. Or closer to the mark: they didn’t even realise they owned the cow in the first place.

Two years later the developing shift in power relations continued when Sky TV UK was told (note that word), that to be able to cover the England team in India, a Hindi-speaking commentator would also need to be a part of the commentary team. Bose himself was chosen, and for the first time, viewers were introduced to a button on their remote control that let them switch to an alternate commentary. That same year (1993) a happening occurred that left followers in no doubt that the self-appointed guardians and custodians of cricket, the English and the TCCB (the Test and County Cricket Board), were steadily losing their century-old hold over the sport…

A Defining, Deafening, Dalmiya Crescendo…(1993-Early 2000s)

Inzamam Ul-Haq’s demolition job on New Zealand in the 1992 World Cup semi-final on Eden Park curiously also set up a shift in the balance of power stakes. Because after Pakistan had vanquished England in the subsequent ‘92 final and given further cricketing credibility to the growing subcontinent, it set in motion a chain of events where England were also vanquished in the boardroom, with a prior understanding being cast aside by the united boards of India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, who in 1993 stunningly won the hosting rights for the 1996 World Cup at the last possible minute.

It was achieved through the smart strategy of targeting the ICC’s (The International Cricket Council) associate members. No doubt operating by the proverb of ‘Every man has his price’ the smaller member nations were specifically sought out. (Bose): ‘In the past these members had been shunned by cricket’s Test-playing nations and treated like country cousins. Now they were promised one hundred thousand pounds if they voted for the subcontinent, forty thousand more than England offered’.

(Hmmm; one-off, targeted payments to weaker member nations with the unashamed goal of securing their votes for World Cup hosting rights- does it not remind you of a more global sport and their World Cup? And yet, I don’t seem to remember too much wailing and gnashing of teeth over that cricketing version. Tongue-in-cheek, everyone must have been well sick of England running things by then).

In professional sport at the turn of the century and now even more so, money is king and sentiment is probably viewed as more for the weak or misguided. Therefore when an administrator with a sharp eye for the main chance named Jagmohan Dalmiya from the BCCI (Board of Control, Cricket India) got involved with the 1996 World Cup, it was destined to return a bucket load of profit to stakeholders, including the no doubt suitably impressed ICC. (Incidentally, Dalmiya was the person in 1991 who first proposed re-admitting South Africa to international cricket).

In fact the 1996 event wiped the floor with the amount of income it generated compared to 1992. As an example, Bose mentions that just to win the right as the official drinks supplier and not even be counted as a main sponsor, Coke had to pay above what Benson and Hedges did when they became the exclusive naming rights sponsor for every match in the entire ‘92 tournament. The tobacco company Wills was back again as the main sponsor after their first run in 1987. Health-conscious governments weren’t exactly in vogue back then. In any case, Wills paid four times what B & H had in 1992 for exclusive naming rights.

The 1996 World Cup became a genuine cash cow and was a watershed moment in light of what was to follow. The boards of India and Pakistan who had jointly underwritten it, both pocketed fifty million US dollars at its conclusion. Quite a pretty penny. Sri Lanka was a risk as an underwriter due to the civil war that was raging on at the time, and didn’t join in with that aspect.

Because of this roaring success and as its driving force, Dalmiya would have had an extremely powerful base from which to further his ambitions. And so it proved- with very vocal support from Sri Lanka as well as naturally his own nation, Dalmiya ascended to the presidency of the ICC, the highest job in world cricket, in 1997.

However his election was to become extremely protracted and intensely fought. In the original ballot in 1996, he won but had failed to achieve a two-thirds majority necessary under the ICC constitution. What followed, according to Mihir Bose, was a battle so bitter that ‘it created scars that have still not healed’. Bose explains it was an election process that began at Lords, went on to Singapore and finally ended in Kuala Lumpur before Dalmiya was eventually and seemingly quite grudgingly confirmed as the first Asian, and first non-cricketer to assume the ICC presidency.

Once that angst-ridden dust had settled, the ICC started to generate large sums for the first time ever. Dalmiya literally ‘began to harvest television income’ (Bose). He also came up with new ICC initiatives like ‘The Champions Trophy’ (which NZ won in 2000; to date our sole senior men’s international trophy).

Just how lucrative the television industry was suddenly becoming for the ICC was fully illustrated in, of all places, Paris in 2000. In the course of ICC discussions held in the French capital for the purpose of allocation of future World Cups and other tournament hosting, Bose states that this particular meeting ‘…showed how the money Dalmiya had brought had changed the game’. This is no better shown than in this incredible statistic from Wikipedia: When Dalmiya took over as ICC President in 1997, ICC had funds of £16000 and when his term ended in 2000, it had over $15 million.

It was Dalmiya-driven money that held centre-stage at one the most extraordinary meetings in modern sports history. The upshot being that a while after, the ICC split itself into two entities; almost certainly because the British Government had refused them a tax status exemption on their new-found wealth. All of the television revenue and other streams were directed into an overseas company and account. ‘The UK-based company, which continued to operate from Lord’s, did not make any money and therefore avoided paying tax’ (Bose). Basically the ICC had become tax-exempt.

In a natural follow-on from Paris 2000, in 2005 the first of two happenings indicated that the cricket world had changed for ever. This was when the ICC moved their base from Lord’s in London after existing there for the previous 96 years, and re-located to the deserts of Dubai in the Middle East. Even at the turn of the millennium such an outcome would have been unthinkable. This was hence also unthinkable from 2009 in Abu Dhabi (and I bet you thought pink ball cricket was a recent innovation):